Angela Maria Morais Souza – Anacé

My name is Ângela Maria Morais Souza, I am 52 and live in the municipality of Caucaia, Ceará state, in the village Taba dos Anacé Indigenous Reserve. Speaking of Covid-19 leads us to the upheaval caused by the disease; many people became infected, some recovered well, others suffered more, and we lost a great many. For us here in the Reserve, it was a difficult time and it had a huge impact, because we lost a beloved member, a strong leader in our village, it was an intensely sad moment. There were a number of illnesses, not just physical but also psychological. Many people got sick and, even today, the situation of the village is quite precarious, because of everything that happened.

When discussing Covid, we also recall the impact it has had on our education, on our Right to Learn Indigenous School of the Anacé People. Covid continues to cause huge problems. Here in the village, teachers have to give remote classes and take homework to the children, who have to return it to be graded. The situation has impacted the children’s education. They miss the personal contact and being together. The situation is strange. Some understand without difficulty, but others have an enormous problem. This lack of contact that we need with the children – teacher with child, child with teacher – affects us psychologically, we miss the life that we have, being together.

The isolation has brought a series of difficulties that are hard to grasp. It’s very hard for people not to have contact with their parents, to be unable to be together or hug one another. When a beloved person died and we were unable to attend the funeral, it was very difficult. We are accustomed to attending funerals and being together at that moment. This was a year of many upheavals in our lives, not just among the Anacé, I think, but all over the world.

For this reason, we need to be very careful about everything associated with this problem. We have special health needs, and the clinic here on the reserve has taken every precaution: scheduled appointments with doctors and nurses, avoiding gatherings, and being careful to use masks. We erected barricades and a gate, which are still up in our village. We had to take these measures to avoid another death, and another and another. Today it’s easier, cases are on the decline, but we still remain careful and cautious, so that we can get past it, and say that though we went through this, we at least made it to the other side.

Josenir Policarpo Ribeiro and João Gleidson dos Santos Oliveira – Anacé

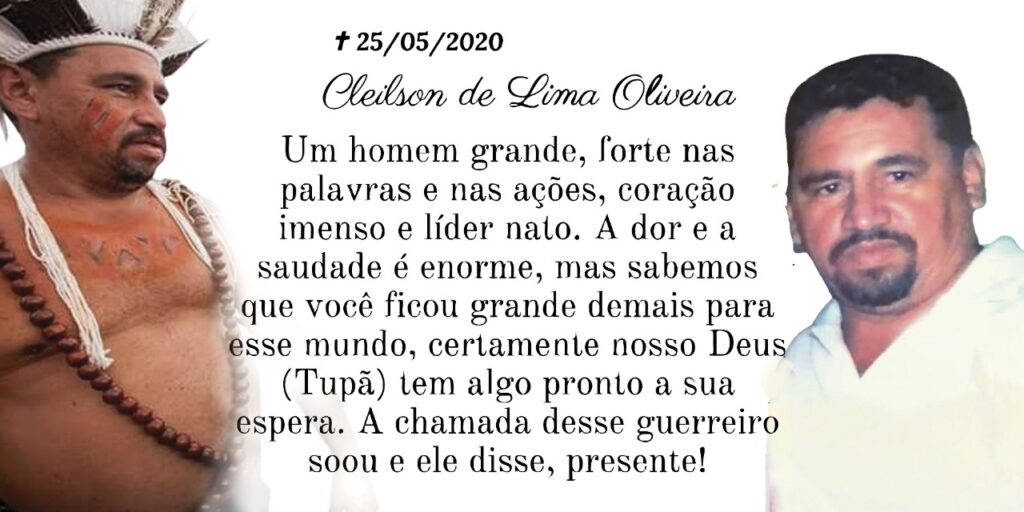

Josenir – My name is Josenir. I am known as Josenir Anacé, widow of Cleilson Anacé, one of the great leaders here in the village, who really took a stand, with decrees (internal ones, established by the community), so that this disease wouldn’t get to our village, our Indigenous reserve (the Taba dos Anacés Indigenous Land ̶ TI). Unfortunately, however, as we all know, it is an invisible virus that does not choose its victims. It’s a very painful loss. He wasn’t just one more, he was the father of my children, my husband, a leader missed by the whole village. So, I can’t say that he was just one more.

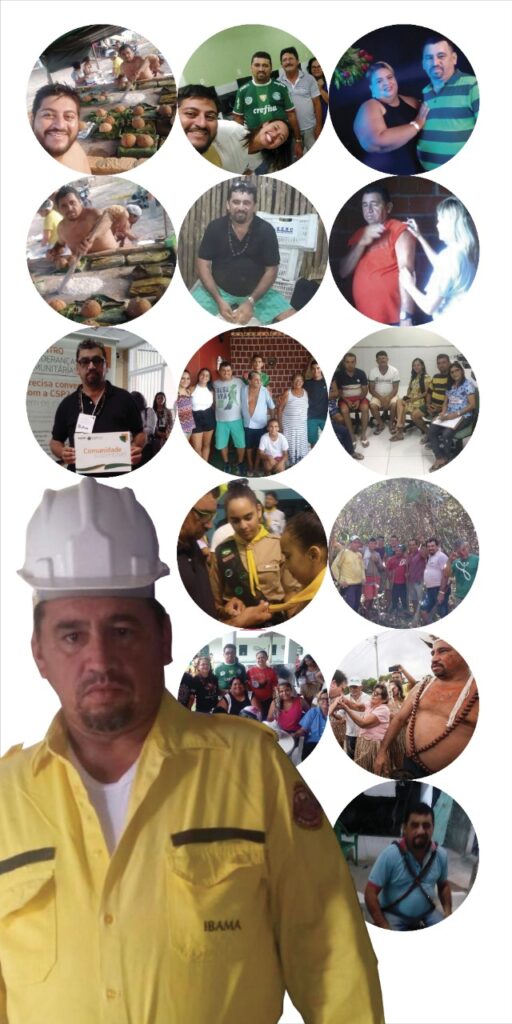

When he had Covid-19, we all also had it. We got treated. My mother had it, my brother-in-law, my children, but thank God, it’s decreasing, it’s been worse. We’ve all had the symptoms. My daughter Yane and Yasmim, who is the youngest, had no symptoms, but tested positive. Covid-19 impacted everything. Just by losing my husband…everything was affected, absolutely everything. Like I said before, it was a loss that shook up everyone here. Today, the leaders are in mourning. The leadership commission, the brigade, in which he (her husband Cleilson) participated, are in mourning today. He left a legacy here on the reserve, he fought a lot. He was one of the leaders responsible for us being here today. The struggle has lasted over 20 years, and he was always at the forefront, mainly when it came to the construction of these houses.

When the issue of this pandemic arrived, he took the lead. With all of the health problems he faced, he suggested a sanitary barrier, which we still have today. He stayed at the gate, where entry [to the Indigenous Land] is controlled. The decree was issued precisely so that only family members could be here inside. He went from door to door, from house to house ̶ not only him, but also the brigade, along with the other leaders ̶ and managed to allow only family members [to come] here.

João Gleidson – My name is Gleidson Kuarasaiaqua. I am a youth leader of the Anacé. I am a student, a university student. One of the huge setbacks of this pandemic, in addition to the various limitations, is the “new normal”, as we call it, in which we leave our comfort zone. There was a time in which we couldn’t even go out in the street. One of the huge impacts of Covid-19 on my family, and the Anacé, was the loss of my father, the leader Cleilson Anacé. As my step-mother said, it (Covid-19) doesn’t choose social class, doesn’t pick who will contract it, who the people are. We don’t know the severity, so anyone can catch it, and anyone can pass away. We saw that, from the eldest to the youngest were affected by this virus, from the richest to the poorest, in the most isolated and most exposed communities.

The Anacé movement is almost as old as I am. It is 21 and I am 20. My father said what I have to do among my people. I am on the outside acquiring white peoples’ knowledge, but I have to return back here inside and show my people what I have learned and continue as a leader, which is not an easy role. My father left this legacy, of saying that I must fight for my people, for the rights of my people. This is a legacy that he left me, as an Indigenous youth. If I am the person I am today, I owe it to him. He taught me everything that I am, everything I know. Today I am here, looking at photographs of him here, of moments, and a flood of memories comes. The legacy that remains here today is that I must fight for the rights of our people. If we are here in the Taba dos Anacés IT [Indigenous Land], in our homes, living near one another, able to show our cultural manifestations, able to live our culture, live as Anacé, live with this identity, then, we Anacé, will perpetuate our culture.

I believe that this pandemic, however severe it may be, all over the world, has taught us to see life in a different way. We see that these numbers here today in our country, of deaths, aren’t numbers, they are people, they are families. So, we learned to value more what life is and the meaning of life. Do we really see others to be living? These numbers that were collected aren’t just numbers, they are families, are constructed histories. So, today I believe that, after this, this experience that was not easy, we can look at life in a different way, not just our own lives, but those of others as well.

Josenir – As much as this pandemic has really brought families together, we already had this legacy. We always had this harmony, this unity. So, the loss of Cleilson was very painful, because, at the time, the family couldn’t be together, no matter how close we were.

João – This period was very difficult for us Indigenous people. I think it really pointed out the situation of the Indigenous and the indigenist policies of this country. What happened to our relatives in the Amazon, for example, in Alto Xingu… To see many leaders and relatives dying, [who were] living cultures and books…This really reveals the current situation of indigenist policies in Brazil, and confirms how much struggle we have before us. Our fight is no small thing…and (it reaffirmed the importance of) occupying Indigenous spaces in different spheres, and gave direction, so we know how to fight.